No wonder Irene develops a soft spot for poor Bachhuber, who is such a different type of man: crucified by his sexual yearning, poisoned if he ever drinks alcohol, melancholy and gentle and gullible. (His backstory is a feast in itself, with his history in early aeronautics and party tricks with gelignite.) Once Dan is dead, however, Titch begins to develop his own patriarchal swagger, hanging out in bars with the loud power-brokers, imitating their boozing and womanising. She has loved and supported tiny Titch through the early years of their marriage because she hated how he was bullied by his braggart of a father, Dan. Irene is plucky, capable, generous and impulsive. Irene and Bachhuber narrate the novel’s story in more or less alternating chapters, and part of the narrative is the growing attraction between them.

#A long way from home peter carey how to#

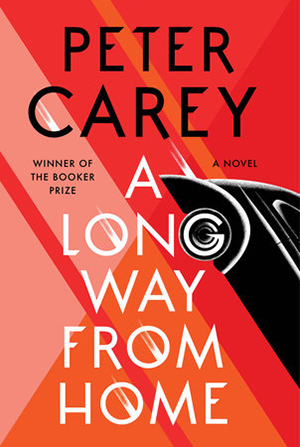

Carey relishes all the detail of their preparation: Irene worrying about the dust in the outback clogging the Holden air cleaner, stretching a stocking over its wire mesh as an extra filter Titch showing their neighbour Willie Bachhuber how to “remove the shackle bolt from the leaf spring”, jacking the spring up “so the eye moves along the wood to the spot where the shackle can be fitted”.īachhuber navigates: brilliantly, because he loves maps and once worked as assistant to the map librarian of the state library. Driving a car is all in the bum, he unromantically explains, “and her bum is a perfect instrument for the job”. Titch Bobs is the best car salesman in rural Victoria, and enters the trials as a publicity stunt for his new car showroom he takes along his wife, Irene, mother of their two children. This novel is his opportunity to write with love about both the landscape and the engineering. (Feb.Carey’s parents ran a motor business in Bacchus Marsh in Victoria, where the book begins: as a boy he followed the trials with passionate enthusiasm, and he understands their romance from the inside – testing the genius of the cars’ engineering, and the ingenuity and skill of the drivers, against Australia’s raw and resistant natural landscape. This won’t go down as one of Carey’s better efforts. Carey’s prose is cutting and often quite funny (“On the far shore stood a moustached white man who should have been told, years ago, don’t wear shorts.”), but that alone doesn’t save the overly shaggy story. Carey takes a lot of time setting up his narrative chess pieces, and it’s not long after the race starts (over a third of a way into the novel) that a family tragedy breaks up Titch’s crew and eventually sends one of them on a baffling adventure that unearths a life-changing secret and lays bare the shameful history of indignities perpetrated against Aboriginal people. His crew: his wife (and driver) Irene, and his neighbor (and navigator), quiz show champion Willie Bachhuber. In postwar Australia, car salesman Titch Bobs decides to enter the Redex Trial, a grueling endurance car race around Australia, with the goal of winning and using the ensuing celebrity to open his own dealership. Carey’s unfortunate latest (after Amnesia) starts out being about a race and ends up being about race, but it’s marred by so many “what’s going on here?” moments and convenient plot-changing contrivances that readers will wonder what story Carey’s trying to tell, and how.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)